Every August, as summer began to tip toward autumn, Elizabethans marked a feast that was older than Christianity itself: Lammas, or in Old English “hlāf-mæsse” meaning “Loaf-Mass.” By the 1560s, England was a Protestant nation under Elizabeth I, yet villagers still carried echoes of pagan and Celtic ritual into their daily lives. Lammas was one of those liminal festivals where old magic, Christian faith, and folk tradition overlapped, making it one of the most evocative celebrations of the seasons of an Elizabethan year.

🌾 Origins of the Feast of First Fruits

Lammas fell on or around August 1st, timed with the first cutting of wheat. Its roots lay in Lughnasadh, a Celtic festival dedicated to the god Lugh and the harvest. Lughnasadh (pronounced LOO-nuh-sah, also called Lughnasa or Lúnasa) is an ancient Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season around August 1. Its name comes from the god Lugh and násad meaning “assembly” or “gathering” or possibly nás “death.” It was one of the four great Celtic fire festivals with Samhain, Imbolc, and Beltane which marked seasonal transitions.

500 years or so later, after the rise in Christianity, in Elizabethan villages, the day was marked by bringing the first loaf baked from new grain to be shared or blessed. This was often at a Church service (yes, another adopted ancient festival!). The bread was a symbolic offering to ensure the rest of the harvest would be plentiful.

Afterwards, tables were set with early fruits and berries, cheese, butter, pigeon pies, and honey cakes. Ale brewed from last year’s barley flowed freely. Villages often held fairs, wrestling matches, races, and even trial marriages called handfastings, a practice with distinctly pre-Christian undertones.

This misericord at Ripple in Worcestershire shows the first Lammas loaf in the communal oven, being guarded by armed men – such was its importance.

The Lammas loaf itself doesn’t appear to have been any different from a normal cob-style loaf – it’s significance was more symbolic by the Elizabethan age.

(Image credit – Hugh Williams – The Mystery of Mercia)

🔮 Magic, Belief, and Witchcraft in the 1560’s

The Elizabethan world was still alive with folk magic. For the ordinary villager, the success of the harvest was not only a matter of hard work and weather, it was also tied to the unseen forces that governed luck, fertility, and the favour of God.

– Charms & First Sheaves: The first bundle of wheat, tied and set upright on Lammas, was believed to hold protective power. Farmers might keep a Lammas sheaf in the house or barn to safeguard against bad luck. I can’t speak for how successful it was, because during Elizabeth’s reign there were frequent and long spells of bad or freezing weather.

– Bonfires & Spirits: Nighttime bonfires, a survival of pagan solstice rites, were thought to drive away malevolent spirits who might blight the fields.

– Witchcraft Fears: The 1560s followed decades of suspicion, which built up to a frenzy of witch hunting under James VI’s rule. A poor harvest could easily spark whispers of witchcraft. An unlucky cow, spoiled butter, or mouldy grain might be blamed on a neighbour “with the evil eye.” Lammas, with its focus on fertility and crops, was a time when such fears bubbled close to the surface. The Elizabethan state itself was deeply concerned with sorcery. Statutes against witchcraft were passed in 1563, making the practice punishable by death if harm was proven. At the very moment villagers were singing, dancing, and offering sheaves in thanks, Parliament was debating how to punish those accused of using “invocations and conjurations.” Lammas therefore existed in a tense religious landscape: a joyful communal feast shadowed by anxiety about the supernatural.

In Elizabethan England, Lammas was more than a rustic feast. It was a ritual moment where pagan memory, Christian practice, and fear of witchcraft met on the same stage. For the village, it meant food, song, and celebration. For the anxious, it meant a time when magic might tip the scales of fortune. For us, it is a window into the complex world of the 16th century — where every sheaf of wheat carried both nourishment and mystery.

Bringing Lammas to life in ‘As Above, So Below’ – a cosy historical fantasy

I came across the festival while searching for a suitable time of year to position my cozy fantasy story and it immediately felt right. A community gathered, celebrating an ancient tradition but with a ‘modern’ Protestant Church twist. The book is set in late 1566, a year when England’s harvest, for once, was reportedly better than previous years had been.

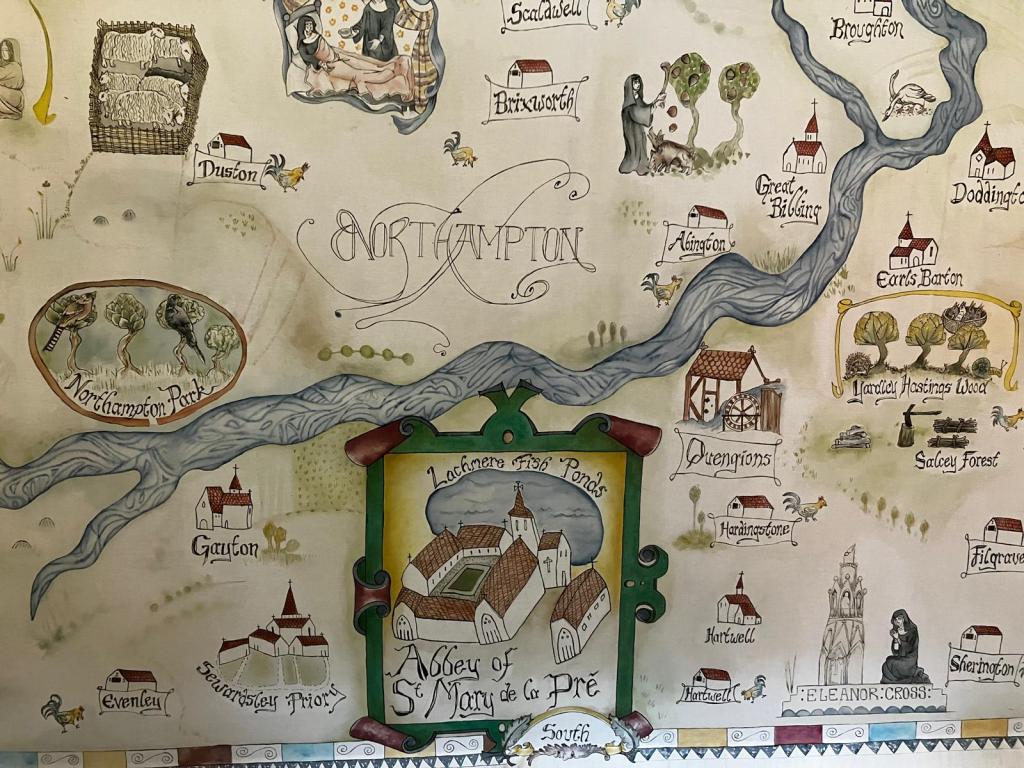

Cozy fantasy, as a genre, often takes place in a small community, and I based my book in the old village of Hardingstone in Northamptonshire, not least because it has a 1000-year-old church (pictured above) and an interesting historical past with the Delapre Abbey close by. I visited the village to ensure I could portray its essence as well as its geography correctly, and found myself utterly charmed by it.

In As Above, So Below, Becca, the village lavender (laundress) encounters some difficulties when her magic appears midlife. She’s forced to seek help from the local witches to try and rid herself of her unwanted power and solve the disastrous effects of her affliction. She’s invited along to the witches’ (pagan) blessing (honouring the old ways), but it’s during the village’s Lammas celebration that the problems really rise to the surface, culminating in an immediate (and stinky!) embarrassment which lingers to affect the entire harvest. You can find out more and enjoy a slice of magical realism and Elizabethan life by reading the book at www.books2read.com/asabove

(Below image is of a vast wall hanging in the newly restored Delapre Abbey, near Hardingstone) showing the estates and villages which the Abbey served/owned. I highly recommend a visit as it is also the site of a historic battle during the Wars of the Roses, and played a significant part in the healing of wounded soldiers during WW2 – including having a plane crash land in the meadows to the front!)

📚 References & Sources if you’d like to know more:

– Statute of Witchcraft (1563), made witchcraft punishable by death if harm was caused.

– Thomas Nashe, *Summer’s Last Will and Testament* (1592) references to seasonal rituals.

– James Frazer, *The Golden Bough* (1890) a later folklorist tracing Lammas and Lughnasadh customs.

– Ronald Hutton, *The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain* (1996).

– Keith Thomas, *Religion and the Decline of Magic* (1971) a classic study of witchcraft and belief in early modern England.