Chapter 1

March 23rd 1937. Austria.

My foot pauses on the pedal when I hear the rumble of trucks pulling into the convent’s courtyard below. I glance down at the beige shirt held by the needle of my trusty Kohler sewing machine, then through the small window next to me. Adjusting the shirt to fit the smaller chest for one of the orphans will have to wait, as two jeeps, a covered truck and a long-nosed black car fill the yard below.

Soldiers scramble out, guns cocked. A tall officer steps from the back seat of the car. His face is hidden to me as he pulls his cap low, then straightens his long, black SS coat. I draw away from sight, mouth dry, mind racing. With so many armed men accompanying a senior Nazi, this cannot be a cursory check. As if confirming my fears, the barked order echoes up: “Überall suchen.”

Would they search everywhere? I doubt they will leave out my room. My gaze sweeps around the neat, narrow space. It was once a corridor, but now my bedroom-come-workroom has a chest for clothes and a bed. On the shelf near the machine, I store sewing supplies and fabric remnants. Superficially, it’s just an ordinary room. But, in the middle of the long wall is a faded wall tapestry, which appears to be decoration. The hanging has another purpose – behind it is the locked entrance to the room which the corridor once provided proper access to.

If my bedroom, then the next, are searched, explaining away the printing press would be difficult. The scruffy-looking man who rested there for a few days departed last night, using the knotted rope hanging from the window tucked into the ivy which grows up the side of the building. I pray he left no evidence of his presence behind, but, hearing the hammer of boots marching across the flagstones, I’ve no time to check.

As I push my stool aside and stand, I catch sight of Freddie’s holey socks on the bed – my next project. Where’s my son? My stomach clenches as I dash across the room. Wasn’t it today the children are supposed to be learning about tending to vegetables? I fling the tiny bedside window open and stick my head out, searching for our ever-growing group of orphans and Freddie in the gardens and vegetable patches. No small capped heads are bent over the beds, no sound of chatter or laughter drifts on the breeze.

Under the shadow of the mountain, the grounds seem deserted, but then, I spot grey intruders stalking through the beans. The muzzles of their guns poke through the leaves like wolves’ black noses, peering, searching for prey. What can they be looking for? This is a small convent, dedicated to taking care of orphaned children, although, for the last year, it’s been hard to ignore the comings and goings of late night visitors, and whispered conversations which cease whenever I walk in.

The classroom – the children must still be there. I close my eyes briefly as I shut the window and cross myself, sending the Lord a prayer for us all. The simple action does little to calm me, but then, not born to this Catholic faith, it’s the best I can offer. I have learned the hard way that appearances matter, and, with my sallow skin, dark hair and eyes, I’m accustomed to visibly demonstrating how not Jewish I am now. After being orphaned ten years ago, in this second decade of my life, I follow the religion of my childhood benefactor and current home, and have forgotten everything I was born to. In dark times, Catholicism is safer, or so Herr Franz Weisz said, when he begrudgingly undertook my parents’ wishes and provided a roof over my head. Until, I disgraced myself and ended up here, sheltered by the nuns. I have no desire to take vows, nor could I, but in return for mine and Freddie’s board, I sew, cook and clean.

A cursory, almost habitual, check reassures me there’s nothing to suggest wrong-doing visible, unless you count an old, much-treasured copy of Harper’s Bazaar nestled on top of my clothes in the chest. Satisfied, I rush through the corridors towards the schoolroom at the other end of the building. When I open the door, Sister Marta’s eyes widen and her mouth tightens at the interruption. The children’s fearful white faces swivel to see who’s entered, so I imagine she must know our sanctuary swarms with Nazis and has warned her charges to behave. My gaze is drawn to the front table where Freddie usually sits.

He isn’t there. My throat tightens. “Can I help, Hannah?” Sister Marta’s voice wavers slightly. How hard it must be to stay calm for the children when we both know what’s at risk.

My speech sounds thick as I replied, “I just wanted to….” To what? Check on my son, when all the other children here have no parents to care for them? My stomach knots with shame. I should be protecting them all, like the good Sister is.

“If you are looking for Freddie, he was helping Sister Luisa with his camera, cataloguing paintings in the Chapel. All other children are accounted for here, safe with me.”

I throw her a grateful smile and close the door behind me.

As I look back up the corridor, a soldier stands outside my room. He’s young and skinny, barely a man, and probably no older than I. His expression changes from bewilderment to decisive. “Halt!”

I freeze, my hand still on the classroom doorknob. “Can I help you?” I doubt it, but I must draw him away.

“What’s in these rooms?” He grips the gun slung over his shoulder and waves the muzzle at the doors as he strides towards me.

I want to tell him it’s none of his business, but Mother Superior’s voice floats through my head. “Rebellious behaviour will only get you noticed. Know your place, speak only of what you know and all will be well, Hannah,” was her wise advice upon my arrival here, six years ago and pregnant.

“Dormitories for the orphans,” I said, my head low. “And this is their classroom. They aren’t locked. You can go in them, if you like.” They are kept spotless and I’m certain the worst he’ll find in there is a contraband catapult toy. Go into these rooms, I pray, not mine.

His lips pinch together as I urged, “But please, lower your rifle if you enter the classroom. I’m sure there’s no need to frighten the children.”

He nods at me curtly, then flings open the door nearest him. I take the opportunity to dash downstairs. My steps slow as I cross the stone flags of the entrance hall and sneak towards the Mother Superior’s office. Through the doorway, I glimpse the officer’s leather coattails, flapping as he paces.

“Father Tomas only read what he was given,” Mother Superior said, in a prim voice. Last weekend, the whole convent, including the children and myself, had attended the Mass in the larger Church in town, upon Mother Superior’s instruction. We had all been shocked at the strong opinion – an abject condemnation of the Nazi regime, in what he’d titled, ‘Mit brennender Sorge’. The edict, written by Pope Pius himself in German, was delivered from the pulpit to the congregations of all Catholic churches simultaneously on Palm Sunday. I recall the sharp intakes of breath when Father Tomas paused after reading out, ‘The experiences of these last years have fixed responsibilities and laid bare intrigues, which from the outset only aimed at a war of extermination.’

For those of us from the convent in the congregation, it echoed Mother Superior’s daily caution – each Jewish child we house here must be protected. Their very lives depend on our conspiracy of silence about their origins.

She invokes the authority of the Papal office, said primly, “A Papal Encyclical must be delivered to the public as soon as it is received.”

“I know it must, I was brought up a Catholic myself,” the officer said. “But it is one thing to have an opinion, but quite another to act upon it, as you have.”

A shiver runs through me as I recognise the deep, clipped voice of Pieter Weisz, son of my benefactor. I have not seen him in years. He’d already moved into the accommodation provided for him by the state, when his cousin – and my only childhood friend – Katarina and I faced the consequences of our actions, back in 1932. Pieter would surely know of my dismissal from his family estate, perhaps even why. And, he knows I’m Jewish.

Hide, my instinct reacts, before he sees me. Before I can be his undoing, for he would surely shoot me down rather than risk me telling anyone his father housed a Jew, let alone built the family fortune by taking over my parents’ business upon their unfortunate demise.

Mother Superior sounds indignant. “Act upon what? I’m not sure what you mean.”

“Don’t you? Perhaps within these walls, you do more than pray.”

“Of course. Aside from our work in the community, we have orphans to care for.”

“If I should find any of them are Jewish, there would be consequences,” Pieter said.

“All children are innocents. Surely you can agree, Oberführer?”

“Not all children are, and a Jew is a Jew.”

This antisemitic stance is well known to me. He has clearly risen the SS ranks in my absence, as well as cast aside the teachings of compassion from his faith. His coveted position was the very reason Herr Weisz was so keen to remove me from his house. The SS must be beyond reproach, generations of pure Aryan blood proven, with no hint of association with a Jew.

I should run – now – but my feet refuse to obey. My hands shake… I cannot leave without Freddie.

Inside the office, the paces cease. Pieter said, “I’m under orders to expose those who assisted delivering the Encyclical, then deal with them appropriately.”

Find Freddie and go, I decide, mentally repeating it over and over until my feet finally comply. As I creep past the doorway, Pieter’s voice reminds me of the cold deliberation of his father. “You can imagine my surprise when last night, my men captured a known dissident on the road, close by to this very convent, with copies of the Encyclical on him. A man known for spreading disinformation, for resisting. A radical who seeks to disrupt order in this province.”

Mother Superior gasps. “Whomever he is, whatever he’s done, that’s nothing to do with us. We are a simple religious order, seeking only to do God’s work.”

“After ‘questioning’, the traitor admitted he’d been housed at this very convent.”

Just past the door, I freeze. Under torture, I imagine most people would say anything to make it stop. But, there was a man here, until last night…

Mother Superior said, “We have no men here, Oberführer. Apart from a few young male orphans, there are only women living here, of course.”

“Then it is women, nuns even, who have produced this pamphlet preaching rubbish, which we also found on him?”

The implicit sneer in his voice makes my blood run cold. Whatever was printed, I can only assume the contents are critical of the regime we live under. Why else would it be of concern to the SS?

I clench my hands together to stop them trembling. How had I not seen what was right under my nose? But I know, deep inside, the answer to my own question. Fearful, I had suppressed my curious, rebellious nature. For Freddie’s safety was why.

In the silence I imagine Mother Superior is wrestling her usual inclination to voice the truth with the need to protect us all.

But Pieter isn’t done. “Not only are you harbouring criminals, but abetting their pathetic cause. Which makes me think, what else are you hiding here?” He snarled, “Shall we see? How about the chapel? Lots of hiding places there.”

Urgency to find my son overrides my caution. As I dart down the passage towards the chapel, the office door creaks behind me.

“There’s nothing there,” Mother Superior squeals, unnaturally high pitched. Her voice and the shuffle of her shoes are too close for comfort, but I don’t look back as I slip into the cool recesses of our sanctuary.

I scan the empty pews, chewing my lip. On one side of the chapel, a selection of paintings I’ve never seen before are propped against the wall by the confession booths. “Freddie?” My whisper grows urgent as I tiptoe towards the altar. “Freddie? Where are you?”

“Mama?” He calls from inside the limestone pulpit. As he then stands, his hair pokes above the stone rim, white-blond wisps caught in the sun streaming through the windows.

“I’m coming, stay there!”

Pieter’s voice echoes down the hallway. “There’s rarely nothing in my experience. Where there’s one rat, there’s a nest.”

“Get down,” I hissed as I run towards the pulpit and up the few steps to reach him. “Stay silent until it’s all over.”

He crouches, arms wrapped around his knees, white-knuckled fingers grasping his camera. Relief floods my body as I drop inside the stone booth and clutch him into me. Freddie’s hands shake and I place my fingers over his on the camera in case it rattles. His most precious possession, his only one, is this old Zeiss Ikon Box-Baldur. The metal box was all the rage in Hitler Youth, and passed on to me as a hand-me-down by Katarina just before she left for finishing school. I suppose it might have been Pieter’s once upon a time. Freddie formed an attachment to it from a young age, although we rarely have money for film or to have his photos developed. Of course, he knows nothing of its providence, just likes to take it apart and put it back together again, twiddling the knobs and pressing the trigger with a very satisfying click.

“Resist any more, and you’ll learn the consequences,” Pieter said, closer now.

I bury my head over my son and hold my breath.

There’s an audible bump from by the doorway, then Mother Superior squeals.

“How dare you?” Sister Luisa calls out. She must have been hiding in a confession box, but as I turn my head to look through the pulpit’s entrance, she steps directly into my eyeline. “This is a place of worship.”

“It’s alright, Sister,” Mother Superior replied, but it sounds forced.

Pieter’s shoes click across on the aisle tiles. “Looks like you do have something to confess, Sisters. A fine collection of paintings, I see. Not the usual sort of pictures one might expect in a chapel. These look far too modern. Being something of an enthusiast, I’m always on the look out for works for the Entartete Kunst. That’s the ‘degenerate art’ exhibition, which will soon be held in Munich. Something of a hobby for our Führer, and he looks kindly upon those who support his vision. Let’s see now…”

“See it or seize it?” Sister Luisa snaps back. The woman has no fear. “I’ve heard what you’re doing, taking paintings from people, from Churches even.”

“But it’s so important to show the people the right kind of art, wouldn’t you say? So they might see the truth within. And, you never know what kind of filth you’ll find in unexpected places.”

“I assure you,” Mother Superior’s voice wavers. “You’ll find nothing of interest here.”

“Then why, pray tell, are all these paintings – showing nothing to do with the glory of God – displayed here?”

There’s a shuffle of feet as Sister Luisa disappears from my view, then she said, “I’m simply cataloguing them. They were donated to us, for safe-keeping.”

“Ah, but who did they belong to before, I wonder?” His shoes tick-tick-tick as he crosses the flagstones, closer to our hiding place.

“Stop!” Sister Luisa said. My arms tighten around Freddie.

“Therefore, I conclude these can only be stolen. Or maybe given in exchange for something. Harbouring Jewish children, perhaps, or fugitives. Either way, they don’t belong here, do they, Sister?”

“They are ours,” Mother Superior interjects. Her voice sounds feeble behind us, then she whimpers. I crane my head around so I can see out of the pulpit better.

Pieter faces Sister Luisa, who stands in front of the paintings like a guard dog. “Are you calling me a liar?”

“I would never…” Sister Luisa blusters.

“Oberführer, no!” Mother Superior calls.

“No-one cares what you say. It’s what I say that matters.”

My heart is in my mouth as Pieter’s arm rises. Then I see what was obscured before – the black snub of a revolver blends seamlessly with his dark leather gloves.

“No!” Sister Luisa’s exclamation is drowned out by the shot booming around the room. Before my eyes, she crumples to the ground. I register the click of Freddie’s camera as Pieter swivels on his heel, arm still extended.

“This lawlessness is unacceptable – even for the Gestapo!” Mother Superior exclaimed.

But he sweeps the gun past the pulpit and aims it towards the doorway at the back. I clap my hands over my mouth and clutch Freddie into my chest.

“Resisting arrest, Sister? What if there’s no-one left to tell?”

Bang! The noise echoes briefly, replaced by the receding tap-tap of his shoes as he strides out.

Freddie whimpers in my arms, breaking my shocked silence. I’ve been clutching him so hard it must hurt, but for the life of me, I cannot release my boy. Framed by the pulpit’s carved sides, I can only stare at Sister Luisa’s body. Blood saturates her white wimple. Despite me silently willing her to get up, she is utterly still.

Freddie wriggles. “Shh,” I whispered into his hair.

I am frozen in fear, until I hear a groan at the back of the chapel. Mother Superior! Her moans galvanise me – perhaps she still lives? “Stay here,” I ordered Freddie as I uncurl myself from him. As I stand, he looks up at me. Watery blue eyes meet mine and his fingers tighten around his camera as if it can replace my warm body comforting him. I tear myself away from his gaze and dash to the doorway.

Mother Superior lies, leg twisted awkwardly, on the floor. She holds her hand to her chest, but blood seeps out between her fingers. “Oh no!” I drop to my knees and push my palm over her bloody hand.

Her eyelids flutter open. “Run Hannah!” She croaks out. “Never look back.”

“Don’t try to speak.” I bear down in a vain effort to stem the bleeding.

A gurgling noise comes from her chest and she tries to cough.

Her other arm twitches, fingers reaching for me as if she is desperate to say something more. I bend closer, folding my other hand over her cold fingers. As I grip her, I remember these arms of hers held me as I birthed Freddie. Comforted me as I accepted I could never go back to the Weisz’s and life as I knew it. I long to feel the strength of her embrace again, but, I fear all I can do now is hold her in her final moments. Despite my best efforts, her blood pools around my knees as I sense her heartbeat slow. “Please stay with me, Mother,” I pleaded, “Lord, heal your servant, I beg you.”

But my prayer falls on deaf ears. I cannot call out for help. Can do nothing but hold her hand and be with her.

Her last breath drifts silently from her lips, soft and shallow. Her head lolls, and I know she is gone.

Before I can do more than bow my head with sorrow, gunshots sound from the courtyard. They are the rat-a-tat-tat of machine guns, not the calculated aim of a pistol. I cannot imagine what is going on out there, and I don’t want to find out. We must heed Mother Superior’s warning, so I dash back to the pulpit.

Freddie hunches against the stone, shivering. There’s no time to comfort him; I grab his arm and pull him out. He resists, shaking his head, but I’ve no choice. I scoop him up, into my chest, and, like a limpet clinging to the rock against the waves, his legs wrap around my waist. My bloody palm holds his face into my collarbone so he does not see the terrible cost of resisting. The camera slung around Freddie’s neck bangs against us with every step as I run past Sister Luisa’s body, then Mother Superior’s, and into the empty hallway.

Mindful of the danger outside, I dash up to my bedroom. My heart thumps a warning, my breath fast and too shallow to calm me as I’m greeted by confirmation of my fears: the tapestry has been pulled down, and the door behind it kicked in.

Stunned, I stand motionless, listening to the wind whistle through from the chamber beyond. In the stillness, I sense we’re alone. They have made their discoveries, passed judgement on us all and delivered the punishment, all in a matter of minutes.

Run, Mother Superior said, but, in a moment of clarity, I understand the intention behind her instruction – we can never return. Still clutching Freddie on my hip, I accept in an instant we’ll never come home and make my peace with it. One handed, for I’m not letting go of Freddie for anything, I sling my old school satchel over my shoulder. I rummage through my chest then stuff my papers into the front pocket. Not knowing what’s ahead for us, I grab my mother’s yellow scarf, Freddie’s holey socks, and shove what few pieces of clothing will fit into the bag. I fix the straps with shaking fingers. Sliding everything we now own across my back, I glance out of the window to the courtyard. Freddie whimpers as I turn his head into my shoulder, but I do not want him to see what I fear I must witness.

Below, the flagstones are strewn with bodies, mown down as they tried to flee. Children, nuns. Innocents. Soldiers stand around the walls, lighting cigarettes as they survey their morning’s work. Guessing what happened sickens me.

Then, Oberführer Pieter Weisz emerges from the front door and orders them to pile the corpses and douse them in petrol. The young soldier I met in the hallway approaches him and points towards my window. I pivot away – a mouse does not wait for a cat to pounce, and they will surely come for the press before long.

As I head through the smashed door, my eyes fall on the dog-eared Harpers Bazaar left on the bed in my haste to pack. Girlish dreams I have to leave behind now our mere survival is in question. I reach beyond the windowpane and drag out the knotted rope from the ivy. Then, I climb onto the windowsill, take a deep breath and swing us out. As I rappel down with Freddie on my back, step by careful step, my mind flashes to recall the pages of that magazine, fallen open on a report from Paris’s Spring Collection. I know then where we have to go.

* * *

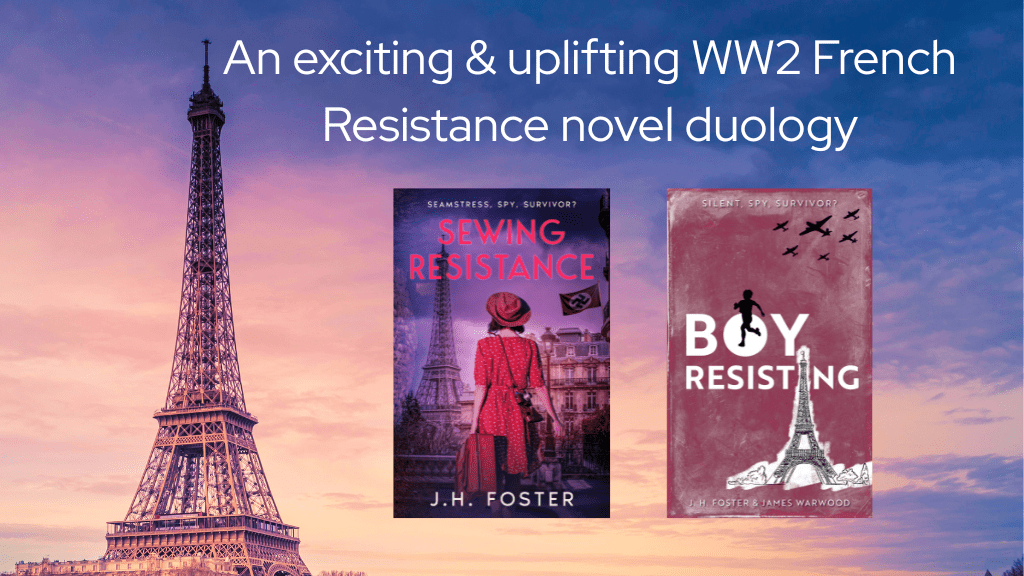

Sewing Resistance will launch in September 2025 on Kickstarter, along with a companion read for middle grade children, ‘Boy, Resisting,’ which tells the tale from Freddie’s point of view. Follow the project to find out more.

Subscribe to my newsletter for launch news, to follow the Kickstarter and more stories HERE!

#firstchapters #sewingresistance #rebelsandresistance #ww2 #history #frenchresistance #occupiedparis