Chapter 1 – The Voice

My name is Frederick and I have a secret. Want to know what it is? Of course you do IF YOU’RE SNOOPING AND READING THIS!

My Mama gave me this book for my birthday. “So you can keep a record,” she said. “It’s important to remember who you are, and what happened to you. Write in it. Doodle. Whatever you want.”

I think she meant write about the Nazis, because they’re why we came to Paris. Because they were after us. That’s the secret… not really!

You see, I’m a nobody. Insignificant. Just a boy. If you knew me at all, then you’d also understand, I’m not so stupid. If I did know anything dangerous, I wouldn’t write it down. There’s nothing important, no secrets you’d be interested in here.

Unless, I am the secret… got you again! Or have I…

Mama’s not so good at reading and writing. She says the words all jumble together, so I’ll write what happened here, for us both. I’ll practise my drawing too, because sometimes a picture can show better than words. And, I like drawing.

I doubt I could ever forget what happened, because I’m good at remembering, but maybe Mama will. Someday we might read this notebook together and remember. Maybe she’ll disappear, because that happens to people too, and then what happened to us won’t matter. Except to us. Or, maybe I’ll die and she can use this book to remember me by, like a story.

Not to shock you, and I hope you’re not as unlucky as me, but… I’ve seen dead bodies before. I wish I hadn’t. It’s only fair to warn you, IF YOU’RE READING THIS, I might talk about them. THAT’S NOT THE SECRET, but how I saw them and why could be.

I was born in a convent in Germany, well, Austria, which was a part of Germany then. I liked it there with the other children, my friends Zachariah and Emily. And Gustaf and Wilhelm, until they both went to new families. Last year, lots more children arrived, but hardly anyone went to new families. Before you knew it, the bunk beds were full! The nuns were pretty nice and tried really hard to look after us all. We had lessons with Sister Marta every day, except Sundays. We played in the gardens and learned how to grow vegetables to eat, and how to take care of the goats.

On Sundays, we all walked into the town to go to Mass at the big church. Twice – once for morning Mass, and again in the evening. We were like penguins, all huddled together to keep warm and look after each other. One fuzzy, fluffy colony keeping the little ones inside for protection. Plus, I sometimes liked to imagine the nuns as giant penguins in their black and while costumes, shuffling around in search of sardines.

As everyone lined up before leaving the convent, Mother Superior would remind us, “You must be good Catholics now,” as if we weren’t always. Sometimes, the newer orphans would be confused during the service. The nuns would whisper to them to keep their heads down, be quiet and do what the rest of us do. I quite liked the singing and the pictures on the walls, even if I didn’t understand what was being said half the time. The smoke from the incense got in my throat sometimes and made me cough – usually at the worst time! I coughed and spluttered and everyone would look at me as if I was doing something terrible, even though I couldn’t help it.

I knew I was the lucky one, though. My Mama lived with me at the convent. Almost all the other children had to leave their parents. Not, I think, because they wanted to. Some people’s parents died and they had to live with us. Having never had a Papa, I don’t miss having one. It’s always been me and Mama, a tiny family within a bigger family of nuns and the orphans. Perhaps we were the largest family in our small town.

Mama wasn’t a nun, because the nuns can’t have babies. She did all the sewing and some cleaning, gardening and cooking. By the courtyard window in our bedroom was her sewing machine, with the big pedal underneath to make the needle whirr and chomp through the fabric. Sewing was probably the only time she sat down, altering clothes so they fitted everyone with a little smile on her face. Sometimes, she was given whole strips of material to sew new dresses, and that made her happiest. I suppose, her work was why she and I had our own room. All the other children slept in the bunk beds, which seemed more fun. When I asked if I could sleep with the other boys too, Mama said, “And leave me all on my own?” She looked so sad.

“Of course not,” I said. “I never want to leave you.” And I thought of all the other children who cried because they missed their families. “I’ll never leave you.”

She smiled then. “When you grow bigger than me, you might think differently. But for now, I’d like to share your childhood.” Then she looked down at her clenched hands and I remembered how her parents had died when she was little and she had to grow up with another family, who didn’t really want her.

“I’ll never grow up,” I replied. “I’m Peter Pan.”

Mama laughed. “I hope not. How awful to never grow up.”

At the time, I didn’t think anything of it, but now I wonder if she knew what was going to happen.

My favourite nun was Sister Luisa. She didn’t try and make me remember bits from the Bible, like Sister Marta and Mother Superior did. When Mama gave me my camera, a Zeiss Ikon Box-Baldur, she looked at the photographs I took and said, “You’ve got a really good eye, Freddie.”

“I have two eyes,” I replied and blinked, because who doesn’t have two eyes? “Which is the good one?”

She laughed at that. When I took the camera apart to clean it, she helped me figure out how to put it back together again. I learned about how to size up the picture you wanted to take by looking through the lens. Each time you snapped a photograph, you had to twist the wind-on knob until it clicked, then the film was ready to take another. When the film ran out, the button would twist and twist until the film negative was safely inside the roll, ready to be processed. Re-assembling was tricky, but Sister Luisa lent me a screwdriver which was better than the knife I used to unscrew it, and a soft cloth to clean the lens with. I’ll never forget her. She told me to hide, and that kept me alive. Hers was also the first dead body I ever saw. You don’t forget a thing like that.

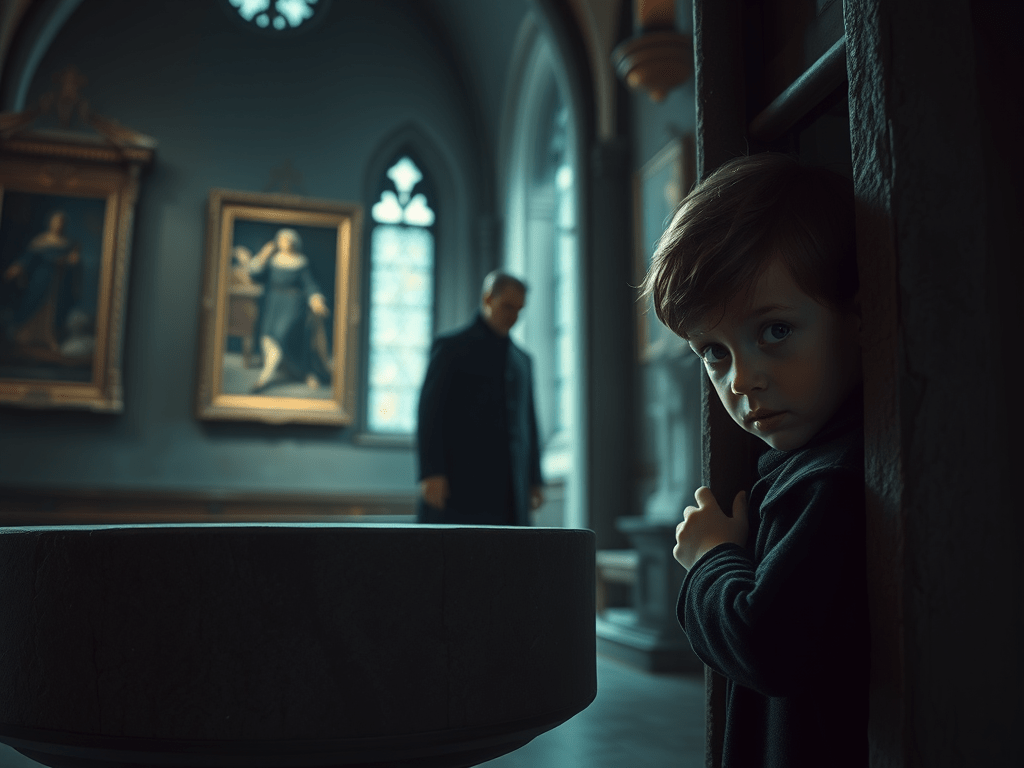

We were taking pictures in the chapel when it happened. Over breakfast, Sister Luisa asked if I would help her with some paintings, given to us for safekeeping. They had been piling up next to the confessional booths for months and needed cataloguing. “Bring your camera. Look on the bright side – you can miss lessons this morning.”

I nodded then nearly choked on my porridge when she handed me a new roll of film!

It was a lovely morning, just Sister Luisa and I, in the quiet chapel. I helped her bring out the paintings in their heavy frames and she told me I was a strong boy. We wiped off the dust then propped each one against the plain stone walls, in a shaft of sunlight so I could take a clear picture of it. Then, we both heard strange, muffled pops from the courtyard. She pushed back her wimple and told me, “Hide in the pulpit Freddie while I find out what’s happening.”

Only the priest was supposed to go in the stone pulpit. “I’m not allowed,” I said, still wondering what the pops outside meant.

“It’s the safest place,” Sister Luisa said, then she glared at me. She didn’t usually frown. “Take your camera.”

“Well if you say so,” I replied, and grabbed it.

“Hurry child.”

I ran across the tiles and crouched inside. It smelt musty and a little bit like stale socks. Then I heard Mama’s voice. “Freddie?”

I stood up and called back to her.

“Get down,” she hissed. I thought she must be angry because I was somewhere I wasn’t supposed to be. I was about to tell her that Sister Luisa told me to, but she pushed me against the pulpit wall. “Stay silent until it’s all over.” It was her eyes which shut me up more than what she said. They were wide and her face was white. She and I huddled against the cold walls and her arms shook. My camera rattled and she clamped her hands on it just as I heard a man’s voice.

It sounded deep and sharp, all at the same time, talking about the paintings. I didn’t really understand what he said, as if there was a layer behind what he said, in that way grown ups do when they say one thing but really mean another.

Mama craned her neck to see out of the entrance gap in the pulpit, but her hand kept my head in her shoulder so I couldn’t move.

The man talked about taking the paintings for an exhibition, for Hitler. Sister Luisa said, “They belong to us.”

Mother Superior was there too, and tried to argue with him as well.

But the man’s voice turned hard as he disagreed. His footsteps grew closer to the pulpit, and Mama’s arms tightened around me.

A loud bang made me flinch.

‘Boy, Resisting’ launches in September 2025 on Kickstarter, as part of a duology with Hannah (Freddie’s Mama) in ‘Sewing Resistance’. Please follow the project here:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/janfoster/exciting-uplifting-ww2-french-resistance-duology

You can read more of Freddie’s story in ‘Boy, Resisting’ which will launch in September 2025 on Kickstarter.

Subscribe to my newsletter for launch news, to follow the Kickstarter and more stories HERE!

#firstchapters #sewingresistance #rebelsandresistance #ww2 #history #frenchresistance #occupiedparis

Wow, I am blown away by both of these books. I would love to read and review them both. These first chapters were awesome and had my full attention, I couldn’t stop reading!

LikeLike

Thank you! I’ll email you about reading and reviewing.

LikeLike